Nuturing

Love of Literacy

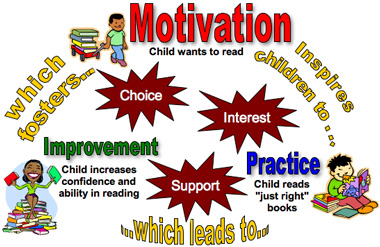

Motivation to read is a critical factor in a child's reading development. Research shows that children who enjoy reading are likely to read more often. Children who read more continue to improve reading skills and overall school performance. Parents and teachers of struggling readers, however, report that fostering motivation to read and write can be a big challenge. |

|

Motivation is the essential ingredient underlying human action. It is heavily influenced by a person's feelings of personal control, competence, and sense of belonging. To foster motivation in struggling readers, teachers must consider the atmosphere of the classroom and its affect on a student's feelings of control, competence, and belonging. Motivation can also be influenced both negatively and positively by incentives or rewards, as well as a student's goals and beliefs.

Teachers can do several things to foster motivation in all students:

Be Mindful of Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Rewards

Intrinsic Motivation

Many researchers believe that strong support of students’ intrinsic motivations, both in school and at home, is likely to lead to lifelong learning and ultimately to enhance student competence and achievement. “Students who are intrinsically interested in a topic are more likely to gain deeper conceptual understanding from their reading (better comprehension) and are likely to have more positive emotional experiences, higher levels of self-esteem, cope more effectively with failure, and persist in their efforts. Students who are intrinsically motivated to read spend more time reading” (Oldfather, 2002).

According to Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET), intrinsic motivations spring from three primary psychological needs: (1) autonomy, or a sense of agency or self-determination, (2) the need to feel competent, and (3) the need for relatedness, or a desire to connect with others and to feel involved with the world. Children must develop a sense of autonomy as readers. A child’s self-concept as a reader involves his or her emotional experiences with reading and confidence. Children naturally have the need for relatedness, to connect with others and feel involvement with the world. Reading and writing are meaningful tasks, full of purpose and opportunities to connect with others and the world. Motivation in highest when children see and experience the value of reading and writing and reasons for these activities.

Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation originates from outside the self, usually involving some kind of reward that goes beyond the activity itself. In many schools, extrinsic motivation to read is developed or encouraged by the use of rewards or incentives. Book It and Accelerated Reader are two examples of programs that employ extrinsic motivation to encourage children to read.

Some educators and researchers have expressed concern that extrinsic rewards detract attention from the actual activity of reading or attempt to control or regulate students' behavior through the use of rewards (e.g., Ryan & Deci, 2000). While extrinsic motivation programs may encourage students to read for a short period of time or to earn a specific reward, their long-term affect on motivation to read is uncertain. In fact, the competitive nature of some of these programs may actually discourage students who may dislike or be intimidated by competition.

Some researchers (e.g., Sansone & Harackiewicz, 2000) suggest that using extrinsic rewards to motivate students to do something they would have done anyway has detrimental effects on performance and on their motivation to perform the activity again in the future. This is more likely to occur if students initially found the activity (in this case, reading) interesting in the first place. On the other hand, the same researchers (Harackiewicz & Sansone, 2000) have also found that rewards that hinge on achieving a specific goal may motivate children when the rewards convince children of their competence. Inspiring a feeling of competence may then increase intrinsic motivation towards involvement in learning activities. For example, awarding a child with a certificate when he or she has achieved a specific goal, such as completing a reading log or demonstrating a certain amount of progress on a reading passage, may boost self-confidence, feelings of competence, and intrinsic motivation.

What We Can Do: Instructional Strategies to Foster Intrinsic Motivation

- Read aloud to your students. Chapter book read aloud is an essential part of the language arts curriculum. During this time, students are able to hear what good reading sounds like and to see what proficient readers do when they come to something confusing or a word they don’t know. This modeling is important for students of all ages. Students also become interested and motivated in reading books similar to one their teacher read to them, or books by that same author.

- Teach the strategy of selecting appropriate books. Spend time at the beginning of the school year teaching your students how to choose a book that is right for them. Description of the 5 Finger Rule. (Also useful as a poster in your classroom).

- Encourage students to read books about their interests. Interest matters. In her study of highly successful men and women who had struggled with severe reading problems as children, Rosalie Fink (1995/96) found that passionate interest in a favorite topic was the one common theme. Each person had a "burning desire" to know more about a favorite topic, and through intense and avid reading practice within that topic, they developed increasingly sophisticated reading skills. Interest played an extremely significant role in these readers' later success. Read more about this study in this online article: Successful Careers: The Secrets of Adults with Dyslexia by Rosalie P. Fink

- Integrate the curriculum. Curriculum is more motivating and students are more likely to enjoy reading and writing when lessons are built around interdisciplinary, conceptual themes. Language arts, science, and social studies can be integrated through inquiry units or investigations based on themes such as survival, jazz, or ecosystems. Through these units, students are guided and encouraged to read high-quality literature, both fiction and non-fiction, which enhances their motivation.

Cultivate Students' Feelings of Control, Competence, and Belonging

Struggling readers and writers tend to develop maladaptive patterns of motivation, such as avoiding academic tasks and acting out to "save face." Especially after years of experiencing difficulty with literacy tasks, they may be very motivated to protect themselves from situations that they perceive as meaningless or threatening. As teachers, we want to help our struggling learners become motivated to engage in meaningful intellectual activities. We can do this by fostering their sense of control, competence, and belonging in our classrooms.

What We Can Do: Instructional Strategies to Nurture Control, Competence, and Belonging

- Provide choice. Resist the urge to limit book selections for struggling readers. Instead, teach all children in your class how to select three different levels of books: "easy," "just right," and "challenge" books. Rereading "easy" books will help develop fluency or could be a perfect selection to share with a younger book buddy. "Just right" books provide just enough challenge so that students will learn some new vocabulary words or find that they need to use some of the reading strategies that you've taught them. "Challenge" books can be enjoyed with a more advanced reader, browsed through, or saved for later. When a struggling reader selects a book that you think is too difficult, ask him or her what type of book it is, and use this moment as an opportunity to teach the strategy of appropriate book selection.

- Reading and writing workshops support intrinsic motivation by providing students with choice, time, and guidance in their reading.

- Book access. Build your classroom library and make good use of your school library and public libraries. You can purchase books inexpensively at garage sales, flea markets, thrift stores, and “half price” bookstores. Children who are surrounded by books and other reading materials and who are read to on a daily basis are more likely to embrace reading and writing in their own lives. How to Get Books for No Or Little Cost

- High-quality and high-interest literature. Learn about and be on the lookout for books, magazines, graphic novels, and other texts that will capture your students' interests, imaginations, and emotions. The lists and websites at the bottom of this page are a good place to start.

- Readers Theater. Drama and hands-on activities are motivating for even the most reluctant readers. Using Readers Theater in your classroom boots confidence, develops fluency, and makes reading fun. More on Readers Theater

- Promote social interactions with books. Provide time for your students to talk about what they are reading. Share with them about something you are reading. Organize opportunities for sharing, book talks, or book clubs (or literature circles) as a part of your classroom curriculum. Some students will initiate this on their own if you have multiple copies of a popular book. You can also structure this more formally as a part of your reading block.

- Employ peer partnerships. Use an "apprenticeship model" by pairing students of differing abilities to work together on reading and writing tasks.

- Encourage students to reread familiar books- It is normal and perfectly okay for students to read easy books or to re-read a book they’ve read many times before. This helps students build fluency, and develop a sense of competence and confidence as a reader.

Recognize the Importance of Goal Orientation and Beliefs

A person's beliefs about intelligence and learning have an important affect on his or her motivation. A student's "goal orientation" will determine how he or she values information and teacher guidance. A student who is learning-oriented tends to be focused on the process of learning and is eager to seek and apply new information and feedback from the teacher or peers. A performance-oriented student, in contrast, tends to be more interested in the end result, such as a grade or completion of an assignment, and is focused on completing the requirements to attain a desired outcome. For struggling learners, developing a goal orientation towards learning is especially important, particularly if they are not be able to perform on grade level.

A student's beliefs about the nature of intelligence can also affect his or her motivation. If a student believes that intelligence is fixed -- that some people are "smart" and some people are not, and there's nothing you can do about it -- he or she may interpret failure on a test or poor performance as confirmation that he or she lacks intelligence. On the other hand, if a student believes that an academic task requires them to use an ability that can be learned, such as a reading strategy, they are more likely to attribute failure to a lack of effort or a poor choice of strategies -- not a lack of intelligence (Molden & Dweck, 2000). If students perceive that a task somehow measures their fixed intelligence, they feel vulnerable and concerned about investing in success. This can lead to a tendency to pursue avoidance-oriented goals like off-task behavior and discipline problems.

What We Can Do: Instructional Strategies to Support Learning-Oriented Goals and Beliefs

- Focus on developing the idea that learning is acquirable. Place more emphasis on the process of learning and improvement than on the final result. Praise students for effort and for using strategies rather than their ability. For example: "You figured out that hard word all by yourself by using your context clue strategy" instead of "You're such a good reader."

- Emphasize that understanding and application are more important than memorizing information for the sole purpose of earning a good grade. Teach students how to measure their own academic progress by using self-assessment rubrics. Engage students in self-reflection by asking them what they have learned about the content of a lesson and what thinking skills they used, as well as what students have learned about themselves as individuals. Encourage students to set their own goals to measure their growth. Praise effort and progress rather than earning a specific grade.

- Don't encourage competition in reading or writing. Literacy development occurs at a different pace for every child. When students begin to measure their success by how well they are doing compared to other children, they become more concerned with avoiding failure and embarrassment than with learning to read. Teachers have used competition as a management strategy for many years, but it leads many struggling readers to believe that reading is a contest they will never win (Winograd & Smith, 1987). Focus instead on helping children measure their own individual growth by comparing their individual progress over time.

- Foster positive self-talk. Give specific praise for actions students take to meet their goals. Point out that students achieved their goals not by luck but by taking specific actions and using taught strategies. Assign tasks that are challenging but achievable. Point out accomplishments rather than focus on mistakes. For an excellent resource about language in the classroom, check out Choice Words: How our language affects children's learning by Peter H. Johnston.

What NOT to do: Well-intentioned practices that may discourage motivation

- Avoid over-emphasizing drill-and-practice worksheet exercises. In a study that compared special programs for poor readers in New York State, Allington and McGill-Franzen (1989) found that an over-emphasis on drill-and-practice worksheets reduced the amount of instruction on reading stories or content-area texts. In fact, they found that less than two minutes of every hour of instructional time was spent on teacher-directed reading of connected text with an emphasis on comprehension. All children, especially struggling and reluctant readers, benefit from wide reading of appropriate texts. A lot of drill and worksheet activities is not likely to raise struggling readers' sagging motivational levels. See whole-part-whole lesson design for ideas on how to imbed skill practice within authentic literature. Keep in mind that it is helpful at times to teach a particular strategy on its own.

- Don't limit book choice. Children need to read books at an appropriate level (see 5 finger rule) in order to practice meaningful reading and avoid frustration. Instead of telling children that they cannot read a book because it is too hard, teach your students to identify "easy," "just right," and "challenge" books. This strategy will empower students to make appropriate book selection independently and foster motivation so that they can read their "challenge" books.

- Don't put struggling readers "on the spot." Reading formats such as "round robin" or "popcorn" reading can place unnecessary stress and attention on struggling readers. Always allow students to practice reading text before they read it aloud before their peers. See Goodbye, Round Robin by Tim Rasinski for lots of ideas on how to incorporate oral reading into your instruction.

|